PORTRAIT

OF A WEIRDO

Tom Friedman at the Museum of

Contemporary Art of Chicago

Stefano

Pasquini

“Hot Balls” could be someone’s exclamation

after seeing some of Tom Friedman’s works in this traveling exhibition.

Instead, it’s the title of one of his works. Lynne Warren, curator at MCA,

writes about it: “The colors are bright, the forms and textures candylike; a

nicely arranged stack of various sizes of bouncy balls, the inexpensive,

common children’s toys. The piece seems inviting, and you move away, thinking

pleasant thoughts, but pause to read the label. The title seems apt, for the

balls are “hot” colors. But there is a bit more information on the label:

“About 200 balls stolen from stores by the artist over a six-month period.”

The innocuous children’s toys suddenly take on a different tenor. Are the

balls really stolen? If they are stolen, how did Friedman manage to take the

big red one? Did the artist himself steal the balls, or did he enlist aid? Is

it ok to steal in the name of making an art piece?”

It is ok to steal for art, Ms Warren, at least in Western societies. Tom Friedman

has finally made it big out of amazingly obsessive works that Michele

Rowe-Shields defined “absurdly brilliant”. And brilliant they are, especially

the works that don’t entail obsessive rolling and cutting but an ingenious

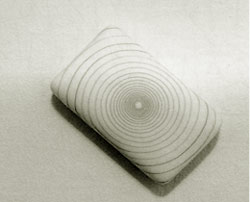

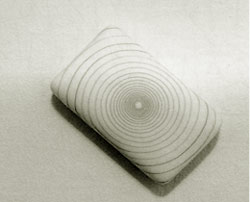

idea worth of Duchamp himself. “Conceptual Art”, continues Lynne Warren, “is

another key influence for Friedman. For 1000 Hours of Staring (1992-97), the

artist stared at a blank piece of paper over a five-year period. The blank

sheet of paper is the ultimate “dematerialization” of the art object, yet it

results from an immense amount of time and effort. Everything (1992-95), in

which Friedman wrote all the words in the English language on a large sheet

of paper, and Untitled (1993-94), a self-portrait carved into an aspirin,

further demonstrate Friedman’s working method. Yet this method is less

obsessive than it is an extension of the American work ethic, which values

intense dedication and pride in one’s work.”

And a lot of laborious method Friedman put in his Untitled incredible self-portrait.

The description of the piece by Jerry Saltz in the Village Voice couldn’t

have said it better: “In the alarming construction-paper rendition of the

artist exploded and collapsed, Friedman looks at space in ways he never has

before. Like the aftermath of a horrible accident, a mangled figure lies

ripped to shreds, one leg bent back, the other separated and lying close by.

(...) Mortality haunts this fragile piece; fascination guides the eye. I was

transfixed by it. Echoing Vesalius's extraordinary 16th-century anatomical

drawings, arts-and-crafts paper projects, World War II and police evidence

photographs, the Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz, a piñata, a medical model,

and Duane Hanson's 1967 motorcycle crash, this sensational sculpture is a tour

de force. Friedman is now thinking about life in the elaborate ways he thinks

about materials, and considering the human body in much more emotional terms.

Moving away from lightness or one-liners, he's taking his art to a more human

place. For longtime observers, this is akin to watching a prodigy grow up

without losing his particular precocious genius”.

Ron Platt, curator of the traveling show, in the catalogue has more to say:

“Friedman follows ideas - and/or materials - to their logical extremes, and

by doing so creates more and more complicated creations. (This can produce

humorous results, as exaggeration often does.) The ideas at play in

Friedman’s work are as complexly organized as his material forms sometimes

are. Just as our mind makes a structure of the random, unrelated information

that bubbles up from our subconscious during dreams, Friedman attempts to

knit ideas into his complex material creations. In some ways, he is

endeavoring to test the soundness of his basic system - to see how complicated

it can get and still keep the viewer engaged, and the art interesting to look

at.” And Friedman’s art is not only interesting to look at, but it engages

you, the viewer, to entangle your brain in physical and philosophical

ponderings you didn’t expect to have to perform inside an art gallery. Ron

Platt continues: “His own quest for deeper meaning through art leaves those

of us who encounter his work more attuned to the world around us and

sensitive to the grand patterns of our lives.”

The concluding point is that Tom Friedman is a weirdo who right now could be

busy stuffing a thousand garbage bags into each other, or playing dough with

his own shit, yet his works are often incredibly hilarious, whilst other

times they hit you in that side of the brain that never gets touched, and

that’s his genius. In this realm of philosophical endeavourings, unexpected

manipulated realities and shockingly moving discoveries, one is left with one

last, fundamental question: “How the hell did he manage to steal the big red

ball?”

|