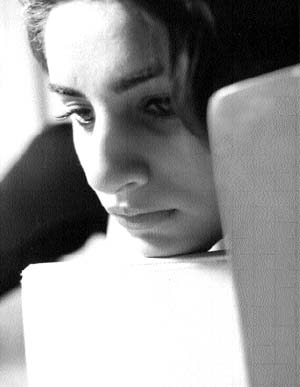

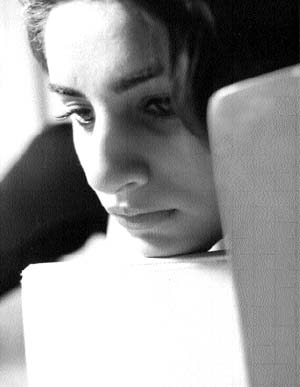

Luay Al Shekli

Portrait, 2001

|

A bridge for Baghdad Unexpected artworks in Iraq Stefano

Pasquini |

|

Luay Al Shekli Portrait, 2001 |

|

|

Art is everywhere in Iraq. Nowhere else I've seen so much public art at every corner of the street. Surely its quality is not always the best, but art plays definitely a noticeable part in the city of Baghdad, yet there's one low point in the monotony of it all: the subject matter. It's the same for all the works you see, the one and only: President Saddam Hussein. I was invited by the Association of Iraqi Photographers, together with a selected delegation of Italian artists, to do a workshop in Baghdad, organized by the NGO "A Bridge For…" that is actively working to help the Iraqi people (not its government) to overcome the difficulties caused by the embargo (mainly an absolute lack of medicines, especially for cancer, which kills 250 children a month thanks to the depleted uranium still massively present in the southern region). Before the invasion of Kuwait, Iraq was one of the richest countries in the Middle East; its economy was comparable to that of Greece, whist now it's closer to that of Rwanda. From the photographers and artists we met, the saddest remark I got was this feeling, above all, of cultural isolation. Their curiosity over what's been happening artistically in the world was overwhelming. Their eyes seemed to tell us they wanted to know all at once, and in their broken English they kept repeating how grateful they were that "The Bridge" brought us here. Even though their way of seeing art as a series of very distinct elements - paintings, sculpture, photography - was obviously still very 80's, some of the artists were very much in line with the contemporary. Above all the painter and photographer Adel Al Tai, who studied art in Paris in the seventies, and it shows. His vision of things is way more open than the one of his colleagues at the Association, who seem to snob him as being just "the artist" of the group. His photographic search began with black and white Man Rayan double exposures, very much constructed within the darkroom, to develop, in recent years, in an intimate research over the powerful meanings that a simple window can obtain. His fabulous "Triptych", shot in Paris during his only foreign trip in a decade, has all the cards needed for a beautiful piece of contemporary art, unexpected from what we (ignorant westerners) think Iraqi art can be. Placed within the art world, the triptych has all the elements of Al Tai's research during the years: the windows, that can symbolize many things but here, above all, I think they reflect the state of the artist (which not by chance is also reflected in the glass): enclosed in this limited body yet able to open to an outside shout, alone and not alone at the same time, exactly in the condition we can experience when, alone in a foreign city, we sit in a museum of contemporary art next to complete unknowns. Considering Al Tai's complete cultural isolation it is remarkable that his work is so contemporary, especially considering that his fellow photographers are still busy searching for the classic composition, and wouldn't have a clue about the meaning of the word installation. It's not by chance that the best results I've seen in Iraq as far as contemporary photography is concerned come from some of his students. Luay Al Shekli is in early twenties yet his portraits have a double poignancy to them. By talking to him we discovered that all his models are his sisters, and he feels quite frustrated by the impossibility to find women to pose for him. Iraq has traditionally been a pretty liberal society - still today not a very high percentage of women wear the chador, whilst this is compulsory to all women in the neighboring Iran - yet it's been increasingly difficult for Luay to ask women to show a liberal attitude by posing for his portraits, especially now that Saddam is fomenting the Islamic cause against the West, producing an increase in the fundamentalist tradition - and some of its bad habits - in the country. Yet in Iraq women don't get stoned to death in public squares, and even though it's a regime, life goes on in a relatively quite way, comparable to Italy during Mussolini's time. People in the street are amazingly polite and friendly, and seem surprised to see foreigners around, especially during a time of expected bombings. This "normality", or at least the deep desire to have the possibility of living a normal life, shows not only in the fixity of the sights in Luay's portraits, but also in the intimate details of the photographic work of Saad Dainal. The series he showed us centered around the color red, a particularly deep bright red that he photographed in details every time he encountered it. The series displays a maturity of thought that again I found unexpected. Looking at the kids begging in the street (not often though, usually next to huge brand new Mercedes cars, that somehow seem to be embargo-free), you'd expect to see from Iraqi photographers a more traditional take on city life, and in all effects this is what we saw at the annual exhibition of the Association. Dainal instead gets closer to the subject, so close at times we don't recognize its identity, forgetting the initial documentative structure of photography, he obsessively concentrates to just one color. We immediately thought of some symbolical, if not political, implication in this research, and when we asked about it he simply replied that there was no implication, just a color choice. We also got the chance to visit the Academy of Fine Arts, and we were impressed by how well it was organized, and how fervent the student community was. Even though the college lacked of funds and equipment we found a lot of students eager to show us their work, and their biggest complaint was the lack of books from abroad. After two weeks, being in Iraq felt like a holiday in an exotic country, and the thought of an imminent bombing was almost forgotten. Only driving back to Jordan I suddenly remembered how people in Italy thought crazy the idea of visiting a country about to be bombed. What is crazy? These are real people, like you and me. |