The enemy is in the house

The meek circus of the 50th Venice

Biennale

Stefano Pasquini

We're entering the age of quantity, and this year's

Biennale shows it. Whilst two years ago the participating

artists were about 300, this year they are over 500,

without counting all the unofficial participants at

Utopia Station and the other exhibits that overwhelmed

Venice in the atrocious heat of the opening days.

After three days of openings and press conferences and

parties, when I was about to leave Venice I thought to

myself: "a circus, that's what this year's biennale

felt like".

Which made me wonder if it makes any sense nowadays to

build up such a huge event, where the fruition of the

works become impossible due to the huge quantity of them:

we're talking about at least a thousand works of art to

view and judge and relate to. Yet it was still a

fulfilling experience; one that made me ponder much more

about the role of the curators than the artists

themselves. Which is, in a way, a paradox, as a paradox

is the fact that the Italian artists invited at the

biennale were not given any money for the production of

the work, no cash token for accepting to participate, no

catalogue. "What? No catalogue?" I asked one of

them when he told me so. "No, just a 20% discount on

the price". "Ok, here's my 40% press discount

for you". That was the least I could do to someone

who spent two weeks in Venice (ok, the hotel was paid

for) to install a work that was not paid by anyone, since

the artist in question doesn't have gallery

representation.

"Dreams and conflicts" had a subtitle,

"the dictatorship of the viewer," and I didn't

quite like that: I don't think in any given time

contemporary art has been so distant from the spectators.

Of course, the figures tell you another story, but ask

people in the street and you'll find that no living

artist is known as much as the crappiest pop star or TV

presenter. These issues are dealt with in the catalogue

essay of Francesco Bonami, this year's curator. He did a

good job, but my main question is about quality; no

particular work stuck in my mind after the three days, no

masterpiece that moved me as much as Gary Hill's

installation two years ago. So many works resembled

pieces by other artists, and some were just blunt copies.

Is it possible that the overall quality of contemporary

art in the world is so low?

Yet his essay convinced me and made me think of Venice as

a utopist island that can make a change in a wrongful

world, a possible alternative or, in fact, utopia.

The arsenale was a diligent mess, work after work after

work in distinctive rooms, with a title and a clear

curatorial view, that peaked in what I really found

amusing: Hou Hanru's Urgency Zone. It starts off

with a funny installation by Yang Zhenzhong, "Let's

puff", a specular video installation where a girl

blows towards the other screen, making a cityscape

fast-forward. Then it starts, works all over the place,

pamphlets, videos projecting from all over the place, a

huge weird sculpture and a strange wooden staircase.  As I climb it the imponent

classical music peaks and I'm on top of the world, I'm

the master of the circus, a perfect reflection of today's

surreal world, with all these art people puffing and

sweating to hurry and not miss anything. Almost a

masterpiece.

As I climb it the imponent

classical music peaks and I'm on top of the world, I'm

the master of the circus, a perfect reflection of today's

surreal world, with all these art people puffing and

sweating to hurry and not miss anything. Almost a

masterpiece.

The Arsenale show goes on to finish in Utopia Station,

messier than anything else, yet quite disappointing. Only

Yoko Ono's little room, where you could stamp anywhere

the sign "imagine peace" with an inkpad was

nice and refreshing.

The Giardini this year was probably the most interesting

part of the Biennale. I particularly enjoyed the Korean

Pavilion, the Japanese one, Olafur Eliasson's strange

architectural world in the Danish Pavilion, but also

Egypt's Ahmed Nawar and his almost naďve installation

about violence and peace, Czech and Slovak Republic's

installation of an Olympic Christ by Kamera Skura and

Kunst-Fu, and outside the Giardini a mention has to go to

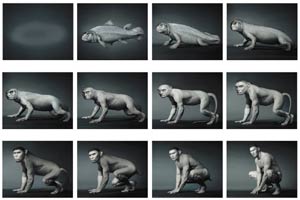

the Taiwan Pavilion with a well thought video

installation by Daniel Lee and photo-based works by Yuang

Goang-ming. Also the Kabakovs' show at Querini Stampalia

was great, if you go to Venice it's a must, and should

need a review of its own.

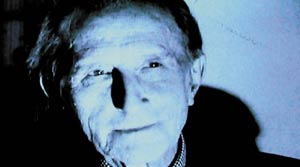

The Italian Pavilion wasn't particularly exciting, or

maybe just too crowded to be appreciated. Some high

quality works were there together with remakes of other

artists' works and a tiny little cherry on the massive

cake: Warhol's Screen Tests of 1964-66, with

Marcel Duchamp behaving just like Marcel Duchamp would.

Probably the most thought out pavilion of them all was

the US one. Fred Wilson's exhibition was all focused on

the presence of black people in Venice throughout the

centuries: from Veronese's paintings to the tacky racist

glass ashtrays everything was there to remind you that

not much has changed all this time: it's 2003 and

xenophobia is still part of everyday life.

At this point I noticed where I was: Venice is the

capital of Veneto, the land of the xenophobic Northern

League Party, in a government coalition together with the

new fascists and Berlusconi's Forza Italia. And

we all know what Berlusconi thinks of other countries,

like the Arab world or the Germans, just to mention a few

of his gaffes.

This is when I realized the true strength of this year's

Biennale: in a world that is boldly going toward the

wrong path this is the utopical island: 500

people saying, all in their weird arty manner, no.

Useful Links:

www.labiennale.org

www.hungryghosts.net

www.krabbesholm.dk

www.odaprojesi.com

www.statelessnation.org

www.lovedifference.org

www.irelandatthevenicebiennale.ie

www.langsdelijn.net

www.querinistampalia.it

www.v2.nl/kinema-ikon

www.mae.es/bienalvenecia

www.britishcouncil.org/venicebiennale

www.cityrooms.net

www.bienale-benatky.cz

From top to bottom:

Athanasia Kyriakakos & Dimitris

Rotsios, "Intron", 2003, Greek Pavilion.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, "Less oil, more courage",

2003.

Vladimir Dubossarsky and Alexander Vinogradov,

"Under the Water", 2003, Russian Pavilion.

Stanislaw Drózdz, "Alea", 2003, Polish

Pavilion.

Daniel Lee, "Origin", 1999-2002.

Martin Kippenberger, "Luftschacht METRO-Net World

Connection", Venice, 1993/2003, Ph. Nic

Tenwiggenhorn, © Nachlass Martin Kippenberger.

Motohiko Odani, "Berenice", 2003, Japanese

Pavilion.

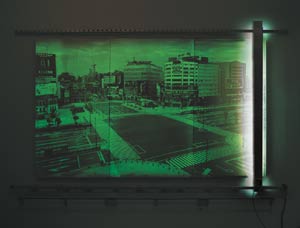

Yuan Goang-ming, "Human Disqualified",

2001-2003.

Andy Warhol, "Screen Tests", 1964-66.

Hou Hanru's "Zone of Urgency", exhibition view.

Kamera Skura and Kunst-Fu, "Superstart", 2003,

Czech Republic and Slovak Republic.

Pedro Cabrita Reis, "Absent names", 2003.

Chen Shaoxiong, "Various ways of

anti-terrorism", 2002-2003.

Fred Wilson, detail of installation at the U.S. Pavilion,

2003.