| Vitriol

Operations Alessandra

Borgogelli

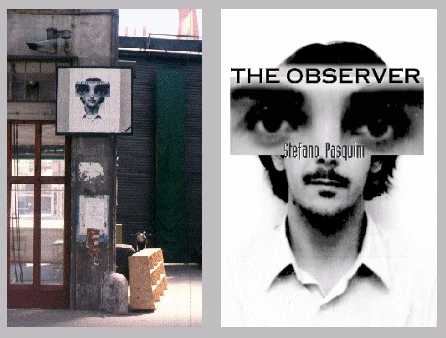

Stefano

Pasquini has a relationship of total detachment from the

average outlook onto reality. Such operation does not

exclude his own critical awareness, it rather strengthens

it. This “detachment” in fact is due to a

strong sense of irony which ensures his distanced stand,

so that he can qualitatively increase his ability in

facing, in a disillusioned and uninhibited way, the facts

of the present with the certitude that the possibility of

a communication still exists. In fact Pasquini’s

incursions in various fields of reality become

explorations of social paradises which, as

“monsters”, are consumed and tossed on the

first page.  Thus sometimes simple photographs collected from

the floor are enormously enlarged and dominate from the

walls of buildings. Or by following an opposite

operation, many elements, the ones which are

“important for all”- and as an example a banal

little statue of the liberty can be used- are reduced to

such a point that they can be found only with a

magnifying glass. It is anyhow a way to always put

precise problems forward: these are the actual truisms,

the obvious and self-evident truths that have the duty to

move our attention from one point to the other, and to

anesthetize the existent. In order to achieve it,

Pasquini confidently resorts to the grotesque and to the

paradox, just to induce an “upsetting” of

meaning. I was thus saying that his are vitriol

operations, that are corrosive of the phenomenological

plane of reality. By going “underneath” they

oppose the obviousness of today’s world as well as

the immense and predictable net of information, since

they act as displacing elements through more effective

visual inputs. In fact, the triggered course equals

Freudian witticisms which have the duty of letting many

certainties precipitate, and of provoking instead, as a

short circuit, an arrest in a sort of lightning of

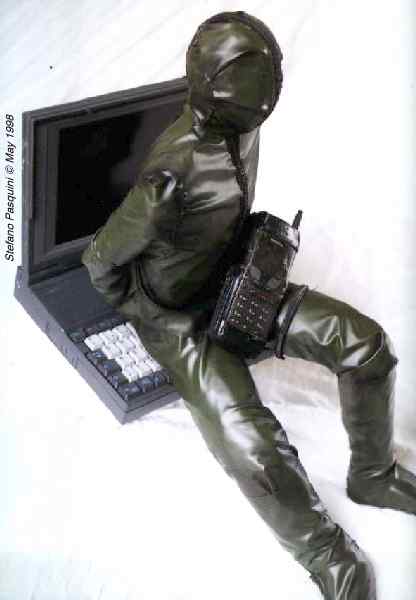

clearness. To reach it, Pasquini often “changes

face” and descends into increasingly different

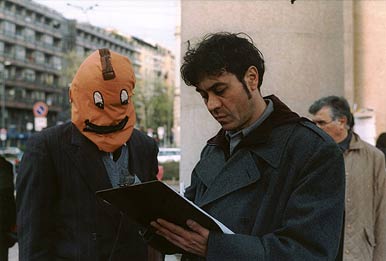

clothes to merrily escape, disguised as Spiderman or as a

banal observer with four eyes or as a mute and

blind interviewer as a “dumb servant” (Questionnaire,

2003). On the latter event, he covers his head with a

pumpkin (as a blockhead, deprived of autonomy and

intelligence). Instead of his mouth he has a closed zip

which underlines the awareness of the impossibility to

communicate. Thanks to his goodness, though, not to scare

us too much, Stefano adds Mickey Mouse eyes. How does the

interview then take place? Certainly not as the same word

would indicate, that brings us back to an operation seen

– as a matter of fact – betwe Thus sometimes simple photographs collected from

the floor are enormously enlarged and dominate from the

walls of buildings. Or by following an opposite

operation, many elements, the ones which are

“important for all”- and as an example a banal

little statue of the liberty can be used- are reduced to

such a point that they can be found only with a

magnifying glass. It is anyhow a way to always put

precise problems forward: these are the actual truisms,

the obvious and self-evident truths that have the duty to

move our attention from one point to the other, and to

anesthetize the existent. In order to achieve it,

Pasquini confidently resorts to the grotesque and to the

paradox, just to induce an “upsetting” of

meaning. I was thus saying that his are vitriol

operations, that are corrosive of the phenomenological

plane of reality. By going “underneath” they

oppose the obviousness of today’s world as well as

the immense and predictable net of information, since

they act as displacing elements through more effective

visual inputs. In fact, the triggered course equals

Freudian witticisms which have the duty of letting many

certainties precipitate, and of provoking instead, as a

short circuit, an arrest in a sort of lightning of

clearness. To reach it, Pasquini often “changes

face” and descends into increasingly different

clothes to merrily escape, disguised as Spiderman or as a

banal observer with four eyes or as a mute and

blind interviewer as a “dumb servant” (Questionnaire,

2003). On the latter event, he covers his head with a

pumpkin (as a blockhead, deprived of autonomy and

intelligence). Instead of his mouth he has a closed zip

which underlines the awareness of the impossibility to

communicate. Thanks to his goodness, though, not to scare

us too much, Stefano adds Mickey Mouse eyes. How does the

interview then take place? Certainly not as the same word

would indicate, that brings us back to an operation seen

– as a matter of fact – betwe en

two or more people, where there is and interviewer and

those who are asked. The interview is mute and thus, if

we wish, not driven, but it is only made by questions

which paradoxically regard “low”, daily

problems, (Which is your favorite word?) or

problems which regard “high” facts (What do

you think of the conflict in Iraq? What is your idea

of perfect Happiness?– with a capital H). It is

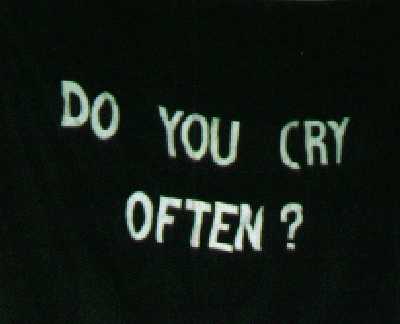

a readymade of commonplaces, powerful sneers of

persuasion induced by actual communication: sometimes in

fact we can read in-between a dry and unproductive

similar question: do you cry often? Imprinted in

flags, the one which are usually meant to express and

display high-symbolical messages. That is how, from time

to time, Pasquini wears multiple personalities by letting

himself go to the continuous flow of the paradoxes of our

society. Like Marcel Duchamp, he never lets out of sight

his own objectives and shows a lucid and sarcastic

intentionality which, from uphill unifies and gives sense

to his various “manifestations” be them

administered by his videos or by his performances or by

his word games or from the height of his flags. One of

the most important points of all these energetic

“actions” is set up by a constant aesthetic

deple en

two or more people, where there is and interviewer and

those who are asked. The interview is mute and thus, if

we wish, not driven, but it is only made by questions

which paradoxically regard “low”, daily

problems, (Which is your favorite word?) or

problems which regard “high” facts (What do

you think of the conflict in Iraq? What is your idea

of perfect Happiness?– with a capital H). It is

a readymade of commonplaces, powerful sneers of

persuasion induced by actual communication: sometimes in

fact we can read in-between a dry and unproductive

similar question: do you cry often? Imprinted in

flags, the one which are usually meant to express and

display high-symbolical messages. That is how, from time

to time, Pasquini wears multiple personalities by letting

himself go to the continuous flow of the paradoxes of our

society. Like Marcel Duchamp, he never lets out of sight

his own objectives and shows a lucid and sarcastic

intentionality which, from uphill unifies and gives sense

to his various “manifestations” be them

administered by his videos or by his performances or by

his word games or from the height of his flags. One of

the most important points of all these energetic

“actions” is set up by a constant aesthetic

deple tion,

and by the consequent anesthetizing operation which makes

the artist, or better the operator, look like a sort of

alien, someone who is different, who stands out from the

average world not quite to record it but to bring it to a

crisis of consciousness, with irony and sarcasm, thus

certainly not by recurring to erudite and heavy

considerations. Such an operation corresponds per

homology to the actual dematerialization where through

the “little” the “much” is induced,

in this case by making a grimace to all certainties given

to us. His sculptural assemblages, so to say, move in

this direction, too. As a matter of fact and from time to

time Pasquini does a shopping list, he places before a

“small program” of purchases with minimum

amounts (Five $4 sculptures, including the price

of the glue needed to fix them for fear they should fly

way, 2003). Such a bricolage is based not on what

we buy and on its consequent aesthetic element, but

rather on - like a bet- is the project, that is the

amount that Pasquini makes available for himself. An

overturning of sense in the finickiness of any possible

beauty. We are dealing once again with a paradox that

teases the artistic product, the same that Pasquini

lively shows in his Unrealizable Projects. That is

how the vivacious small plastic statues “done for

nothing”, stolen for two cents from the world of

jumble sales, of the already made, finally seem to

find their own “epic”. They are unaware

that their function is to negate the epic itself by

invalidating it in the moment of its creation. This is

not in fact a struggle to produce an image, it is a poor

project. It’s like one of those poor shopping lists

that, even without a budget, can create great food and,

above all, bring new energy. tion,

and by the consequent anesthetizing operation which makes

the artist, or better the operator, look like a sort of

alien, someone who is different, who stands out from the

average world not quite to record it but to bring it to a

crisis of consciousness, with irony and sarcasm, thus

certainly not by recurring to erudite and heavy

considerations. Such an operation corresponds per

homology to the actual dematerialization where through

the “little” the “much” is induced,

in this case by making a grimace to all certainties given

to us. His sculptural assemblages, so to say, move in

this direction, too. As a matter of fact and from time to

time Pasquini does a shopping list, he places before a

“small program” of purchases with minimum

amounts (Five $4 sculptures, including the price

of the glue needed to fix them for fear they should fly

way, 2003). Such a bricolage is based not on what

we buy and on its consequent aesthetic element, but

rather on - like a bet- is the project, that is the

amount that Pasquini makes available for himself. An

overturning of sense in the finickiness of any possible

beauty. We are dealing once again with a paradox that

teases the artistic product, the same that Pasquini

lively shows in his Unrealizable Projects. That is

how the vivacious small plastic statues “done for

nothing”, stolen for two cents from the world of

jumble sales, of the already made, finally seem to

find their own “epic”. They are unaware

that their function is to negate the epic itself by

invalidating it in the moment of its creation. This is

not in fact a struggle to produce an image, it is a poor

project. It’s like one of those poor shopping lists

that, even without a budget, can create great food and,

above all, bring new energy.

Alessandra

Borgogelli teaches History of Contemporary Art at the

DAMS in Bologna. She curated historical exhibitions,

especially regarding the Italian XIXth and XXth

centuries, as well as avant-garde shows such as Parole

parole parole (Galleria Civica di Arte Contemporanea

di Trento) on the preponderance of oral and sound events

in art from the Sixties up to today.

FILI IN VISTA

Italo Zuffi

I

treni locali costeggiano gli edifici con passo

rallentato: merletti alle finestre, cespugli curati nei

giardini.

I

treni superveloci costellano di chiazze i bordi del loro

solco.

Ho

memorie dei lunghi soggiorni di Stefano a Londra.

Rispondere al telefono al Royal Albert Hall (un impiego

di cortesia, di buone maniere). Ho immagini della fugace

mostra a Birmingham. Memorie di una performance, nel

corridoio dell’ICA di Londra, nel 1997: odore di

birra e pop-corn.  Odore di

lampade accese e umido aggrappato alle scarpe. Nessuna

parola. Solo questo richiamo dell’artista

all’essere rintanato, travasato in Inghilterra.

Contemporaneamente, fuori, nelle campagne, i cani

addentavano le volpi, tirandole fuori dalle buche nel

terreno in cui si fossero rifugiate. Stefano indossava un

abito da Uomo-Ragno fatto in casa (maldestramente: la sua

qualità). Paziente, incurante del passaggio o della

presenza dei visitatori, dei loro sguardi, del loro

pacato sconcerto, rassegnato attendeva l’arrivo dei

fox-terrier. Odore di

lampade accese e umido aggrappato alle scarpe. Nessuna

parola. Solo questo richiamo dell’artista

all’essere rintanato, travasato in Inghilterra.

Contemporaneamente, fuori, nelle campagne, i cani

addentavano le volpi, tirandole fuori dalle buche nel

terreno in cui si fossero rifugiate. Stefano indossava un

abito da Uomo-Ragno fatto in casa (maldestramente: la sua

qualità). Paziente, incurante del passaggio o della

presenza dei visitatori, dei loro sguardi, del loro

pacato sconcerto, rassegnato attendeva l’arrivo dei

fox-terrier.

C’è

sempre un’attesa per una qualche razza di cani. In

questo gli sono debitore: fatta una scelta, dichiarato

uno scopo, tirarsene poi fuori.

Seduto

sul pavimento freddo, il fazzoletto da naso ben celato da

qualche parte, pronto all’uso. Anche in questo, gli

sono debitore.

Introspezione

resa pubblica: “Do you cry often?”, (Piangi

spesso?), frase ricamata su tessuto e poi stesa

sull’erba, al sole.

Vera

arte sartoriale, la sua, anche se un po’ sghemba, un

po’ sgualcita. Fili in vista. Bordi non proprio

netti. Queste le sue qualità (il non poter rinunciare a

certe imprecisioni, tutte maschili), di cui veste i suoi

manichini (nessuno di essi proviene dal mondo

dell’arte, ma nelle sue vetrine si lascia esporre).

Piangi

spesso?: ma allora si danno per certi i miei pianti,

atti umidificanti.

In

questa stagione percepisco umidità in ogni cosa. Oppure:

ogni cosa si manifesta come rivestita di un velo

lacrimoso.

Stefano assorto, nel

corridoio gelato, nel suo abito rosso cangiante,

inzuppato di luce bianca. Abito self-made (un

paradosso, dopo aver lui così a lungo amato Duchamp e i

suoi “trovamenti”). Stefano intervistatore, per

le vie di Milano, mascherato. Cuciture sgualcite bene in

vista.

|

Operazioni

al Vetriolo

Alessandra Borgogelli

Stefano Pasquini ha un rapporto

di totale distacco dalla gestione normale della realtà.

Tale operazione però non esclude una sua presa di

posizione critica, piuttosto la rafforza. Il

“distacco” infatti è dovuto a un forte senso

di ironia che assicura quella presa di distanza proprio

per aumentare quantitativamente la capacità di

affrontare in modo disilluso e disinibito i fatti del

presente con la certezza che esiste una impossibilità di

comunicazione. Infatti le incursioni di Pasquini in

vari campi della realtà diventano esplorazioni di

paradisi sociali che, come i “mostri”, vengono

consumati e sbattuti in prima pagina. Ecco dunque che a

volte delle semplici fotografie raccolte da terra sono

enormemente ingrandite e dominano dalle pareti degli

edifici oppure, secondo una operazione contraria , molti

elementi , quelli “importanti per tutti”- e

valga come esempio una banale statuetta della

libertà- sono rimpiccioliti a tal punto da dovere essere

trovati con l’aiuto di una lente di ingrandimento.

Comunque si tratta sempre di un modo di mettere in campo

problemi precisi: sono questi gli attuali truismi, cioè

le verità ovvie e lapalissiane ,che hanno il compito di

spostare l’attenzione da un punto a un altro e di

anestetizzare l’esistente. Per fare ciò Pasquini

ricorre con disinvoltura al grottesco e al paradosso

proprio per indurre dei ribaltamenti di senso. Dicevo

appunto che le sue sono delle operazioni al vetriolo,

dunque corrosive del piano fenomenologico della realtà.

Andando “sotto” si oppongono alla ovvietà del

mondo di oggi e all’ immensa e scontata rete

informativa fungendo da elementi spiazzanti , da imput

visivi più efficaci. L’ iter innescato equivale

infatti a quello dei motti di spirito freudiani che

hanno il compito di fare precipitare molte certezze e che

provocano invece, per cortocircuito, una battuta

d’arresto in una specie di lampo di lucidità. Per

fare ciò Pasquini spesso “cambia faccia” e si

cala in panni via via differenti, in modo tale da potere

scappare fuori vivacemente sotto le spoglie di Spiderman

o di un banale osservatore con quattro occhi o di

un intervistatore muto e cieco come un “servo

sciocco”. In questa ultima occasione infatti si

ricopre di una testa di zucca ( da cui

“zuccone”, privo di autonomia e intelligenza).

Al posto della bocca ha una lampo chiusa che sottolinea

la coscienza della impossibilità comunicativa. Bontà

sua, però, per non farci troppa paura, Stefano vi

aggiunge occhi non vedenti da topolino. Come si svolge

dunque l’intervista? Non certamente come ci indica

il nome stesso rimandandoci a una operazione vista

appunto fra due o più persone, dove esiste un

intervistatore e coloro che vengono interpellati.

L’intervista è muta e dunque , se si vuole,

non pilotata, ma è fatta solo da domande che riguardano

paradossalmente problemi “bassi”-quotidiani

( Quale è la tua parola preferita?) oppure

problemi che riguardano fatti “alti”( Cosa

ne pensi del conflitto in Iraq?, Quale è la tua idea di

Felicità- con la lettera maiuscola- perfetta?

). Si tratta di ready made della ovvietà, di potenti

sberleffi alle convinzioni indotte dalla comunicazione

attuale: a volte infatti possiamo leggere in modo secco e

improduttivo frasi del tipo piangi spesso?

impresse in flags , quelle di solito deputate a esprimere

e sbandierare messaggi alto-simbolici. E così, di volta

in volta, Pasquini assume personalità multiple

abbandonandosi al flusso continuo dei paradossi della

nostra società. Come Marcel Duchamp, non perde mai di

vista questi suoi obbiettivi dimostrando una intenzionalità

lucida e sarcastica che, stando a monte, unifica e dà

senso alle sue varie “manifestazioni” sia che

ci vengano propinate dai suoi video che dalle sue

performance o dai suoi giochi di parole o dall’alto

delle sue bandiere.

Uno

dei punti più importanti di tutte queste

“azioni” energetiche è costituito da una

costante depauperazione estetica e da una conseguente

operazione anestetizzante che fa assomigliare

l’artista o, meglio, l’operatore a una specie

di alieno, di diverso che emerge dal mondo normale non

tanto per registrarlo quanto per metterlo in crisi di

coscienza, ma con ironia e sarcasmo, non certo facendo

ricorso a dotte e pesanti considerazioni.

Tale operazione

corrisponde, per omologia, alla smaterializzazione

attuale dove col “poco” si induce il

“molto”, in questo caso facendo uno sberleffo a

tutte le certezze che ci vengono propinate. Anche

gli assemblages scultorei , si fa per dire, si

muovono in questa direzione. In realtà Pasquini, di

volta in volta, fa la lista della spesa, si prepone un

“programmino” di acquisti con importi minimi ( Cinque

sculture da 4$ comprensive del prezzo della colla che

serve a fissarle per la paura che volino via). Un

bricolage così fatto è basato non su ciò che si compra

e sulla conseguente componente estetica , ma piuttosto su

ciò che , per scommessa, il progetto, ovvero la cifra

che Pasquini si mette di volta in volta a disposizione,

può permettere e consentire. Dunque un ribaltamento di

senso nella vanificazione di qualsiasi “bello”

possibile. Si tratta, ancora una volta, di un paradosso

che prende in giro il prodotto artistico, lo stesso che

con vivacità sempre Pasquini ci propina nei suoi Progetti

irrealizzabili . Così le vivaci statuine di plastica

“fatte di niente”, rubate per due lire al mondo

della secondarietà, del già fatto, alla fine

sembrano trovare una loro “epica” senza sapere

però che servono proprio a negare quest’ultima

invalidandola subito proprio già dalla loro

costituzione. Non si tratta infatti di un combattimento

per una qualsiasi realizzazione di immagine, ma di un

progetto povero, che ricorre a una cosalità di

comodo, simile, come accennavo, a quelle liste della

spesa che , pur in economia, vanno alla ricerca di un

“cibo” buono soprattutto a dare

nuova energia.

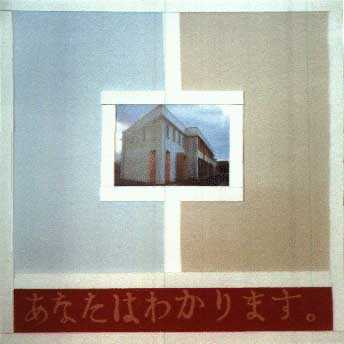

1989-1996

The

work of Stefano Pasquini has always been strongly

influenced by what happens  politically in the

world. In 1989 he was so shocked by the repression and massacre of the Chinese

students in Tien An Men Square that he

painted "China and You", a

symbolical representation of the destruction of their

ideal of freedom. On the 11th of September 1993, he used

his body for an installation to commemorate

the death of Stephen Biko. For eight

hours during the preview of the show, he was chained and

handcuffed, naked on the concrete floor, in the exact way

Biko was the day before his death in prison. In 1993 he

also painted an imaginary "Portrait of the Red

Brigadist", dedicated to the

great engraver Luciano De Vita. In a photographic montage

he represents himself as "The self portrait of

Ernesto Guevara". Other tributes

to political happenings include collages and drawings to commemorate

the desaparecidos in Argentina.

Another painting was titled "The last tv appearance

of JFK". In 1994 he found the group Simone Rondelet together with

Kostas Bassanos, Tiziano Tezza, Cristina Perezzani and

Caroline Creamer. The name of the group was taken at

random from the obituary page of a french paper, and the

computerized image of Mona Lisa soon became the logo for

this fictional artist, whose main aim is to increase

collaboration between different media artists and to be

known and exhibited as a solo artist from Paris, France. politically in the

world. In 1989 he was so shocked by the repression and massacre of the Chinese

students in Tien An Men Square that he

painted "China and You", a

symbolical representation of the destruction of their

ideal of freedom. On the 11th of September 1993, he used

his body for an installation to commemorate

the death of Stephen Biko. For eight

hours during the preview of the show, he was chained and

handcuffed, naked on the concrete floor, in the exact way

Biko was the day before his death in prison. In 1993 he

also painted an imaginary "Portrait of the Red

Brigadist", dedicated to the

great engraver Luciano De Vita. In a photographic montage

he represents himself as "The self portrait of

Ernesto Guevara". Other tributes

to political happenings include collages and drawings to commemorate

the desaparecidos in Argentina.

Another painting was titled "The last tv appearance

of JFK". In 1994 he found the group Simone Rondelet together with

Kostas Bassanos, Tiziano Tezza, Cristina Perezzani and

Caroline Creamer. The name of the group was taken at

random from the obituary page of a french paper, and the

computerized image of Mona Lisa soon became the logo for

this fictional artist, whose main aim is to increase

collaboration between different media artists and to be

known and exhibited as a solo artist from Paris, France.

At the

end of 1994 a very good friend of Stefano, a photographer

called Claudio Serrapica, suddenly died. As a result for

this loss, Stefano made an installation/tribute to a work

Claudio made in the seventies with the help of the povero

artist Pier Paolo Calzolari. The work was

shown at the Underwood Street Gallery of London, and then

exhibited in Bologna, Italy, where Claudio Serrapica

lived most of his life. In the same show Stefano had an

installation called "The second

dream", a reference to Piero Della Francesca, whose death

happened just a few days before Christopher Columbus

discovered the new continent. He also had a series of

unrealizeable projects in which he planned to disrupt the

underground system in

London, to transmit fake satellite news regarding a

Christo wrapping piece, to shoot the walls of a gallery

with a machine gun, to represent death with an

installation of wall graves in two rooms, where in the

second room the spectator can experience death with a

sudden darkness and loss of orientation, to set a tribute

to the 8961 political

desaparecidos of Argentina, (with a Ford Falcon

Car, which was used for their kidnapping) and to start a pirate radio that would pick up gossips from the

tables of Mason Bertaux cafe bar.

His newest works are photographs on the secret of

happiness. The titles constitute the core of the work:  "Working at the Natural

World Carnaby Street shop as a part time sales assistant,

just after having a Benson & Hedges, I discover the

Secret of Happiness" "Walking through Old

Compton Street, listening to the Beatles, having a Benson

& Hedges, I discover the secret of Happiness" and

"Standing by the terrace

at my parents house in Casalecchio di Reno, listening to

Billy Bragg, smoking a Benson & Hedges, I discover

the Secret of Happiness." In june 1995

Stefano took part in Everything Else, a festival

organised by Alternative Arts. In a performance called

"Welcome to London" he

presented himself as Spiderman in the middle of an

identity crises, where he would be reading Sartre's

"Nausea", smelling a jumper and taking

photographs of himself. His latest works are an analysis

of the frustration and lack of communication young and

unsuccessful artists experience in everyday life, like

the flag "Do you cry often?" and

"Like a Bully boy in a

Benetton shop you're never happy with what you've got". "Working at the Natural

World Carnaby Street shop as a part time sales assistant,

just after having a Benson & Hedges, I discover the

Secret of Happiness" "Walking through Old

Compton Street, listening to the Beatles, having a Benson

& Hedges, I discover the secret of Happiness" and

"Standing by the terrace

at my parents house in Casalecchio di Reno, listening to

Billy Bragg, smoking a Benson & Hedges, I discover

the Secret of Happiness." In june 1995

Stefano took part in Everything Else, a festival

organised by Alternative Arts. In a performance called

"Welcome to London" he

presented himself as Spiderman in the middle of an

identity crises, where he would be reading Sartre's

"Nausea", smelling a jumper and taking

photographs of himself. His latest works are an analysis

of the frustration and lack of communication young and

unsuccessful artists experience in everyday life, like

the flag "Do you cry often?" and

"Like a Bully boy in a

Benetton shop you're never happy with what you've got".

|

![]()